Issue #17: Deep Blue

Discussing Sora Tob Sakana's "new" album, the YMO-meets-Johnny's TV comedy trio and the insensitive subgenre of menhera rock

Hi! Welcome to This Side of Japan, a newsletter about Japanese music, new and old! You can check out previous issues here.

CW: Depression, mental health

A casual browse at Japanese rock music in the 2010s might lead you to the descriptor menhera—a shorthand for the manic depressive among other behaviors related to poor mental health. A quick Google search of “menhera rock” will return some blog posts going back to at least 2015, including a playlist made in 2017 at streaming site KKBox compiling songs that fit in this would-be subgenre or another list from last year titled “popular menhera songs for karaoke.”

It’s one thing to group sad songs to get over a break up as the latter list did, collecting songs by Kana Nishino, Ringo Shiina and Aimyon. Labeling the music with a loaded word like menhera, however, is simply insensitive, if not disturbing in the way it flattens depression into a supposedly recognizable aesthetic. But trivializing mental illness in such a manner is a phenomenon perpetuated to this day in Japanese culture one way or another through bands like Milky Way—who frequently comes up in these menhera rock lists—still using it as a hashtag for their new music or the recent viral meme of jirai meiku—a red-based make-up style to mimic the look of a jirai jyoshi, or a girl who appears fine on the surface but actually unstable.

The ease in which menhera is thrown partly has to do with the word’s origin as internet slang. First appearing in the 2010s, the term is a portmanteau of mentaru herusu, or mental health, added with the suffix of -er that was first used to refer to people perusing the mental health threads on 2chan, according to Weblio.

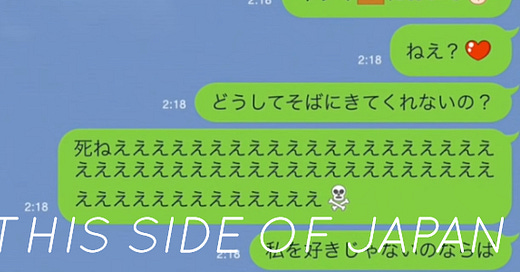

The term made its way into music early on that decade as well. Another popular rock band in these lists, Mio Yamazaki uploaded “Menhera” to YouTube in 2013, and the song illustrates the common sensibilities exhibited by those who get grouped as menhera rock. The lyrical content is more emotionally frank, depressive, and aggressive compared to the average pop song. The verses ignore pop brevity and instead like to go on long-winded. The scrolling lyric video not only gets at how much the lyrics bleed over the margins but also how it resembles raw internet text, either on forums, IMs or iPhone conversations, thrown onto music. I imagine this is how an unlikely candidate like the acoustic-guitar-carrying Aimyon can get lumped into a list like this, through her Line-inspired music video for “Anatakaiboujyunaika ~Shine~”—or “The Dissection of You as a Love Song: Die.”

It’s unfortunate that these artists get grouped under such a crass category because their music itself is valuable in the way it taps into topics then not often found in mainstream pop. Not only do these artists not hold back from voicing emotions like depression, obsession and self-loathing, they present them as ugly and messy as they feel. The guitar riffs are often jagged, sometimes woven in complicated knots, while the singers don’t care if their voices are abrasive compared to the average pop singer. The misshapen qualities as well as their intensity only make the music feel more visceral and personal.

While commonalities within in this type of music might emerge, establishing a subgenre for these works just creates more issues. Identifying these modes of expression as genre tropes flatten the perception of the music. Rounding the artists under a term such as menhera only attaches stigma to not only the types of conversation they start but the methods in which they express those topics. It’s worth mentioning quite a few acts that people fit into this category are either women or voiced by women, who are also subjected to adjacent terms such as jirai-onna and menhera joshi more than men. “When I express sadness or anger, I’m told ‘ you’re menhera,’ when I try to speak with logic, I’m told ‘that’s not cute,’” Haru Nemuri tweeted in 2018. Popularizing the describing of music as menhera only creates more misogynistic ways to shut down art made by women.

During the latter half of the decade, artists whose music get described as menhera seems to have accepted just how vapid the term has become. “I found a tweet recently that said, ‘I’m menhera so I listened to Seiko Oomori’ with a lot of emojis on it,” Seiko Oomori said to Cinra in 2016. “Menhera doesn’t mean much. People who actually take medication aren’t listening to my songs.” The term has taken a similar life to how the word “depression” has been used on social media with ironic distance making it meaningless as much as it made its topics easier to discuss.

The problematic treatment might complicate the perception of the music, but the works of these artists still manage to leave a sizable impact for the future. The more depressive themes seem not only more commonplace in pop but also more accessible in recent years. The conversations stemming from these themes appear on rather unassuming pop at least relative to the more intense music that came before. You can definitely chalk up the change in attitude to the uncertain times, but part of that I think also has to do with these artists who confronted these dark emotions in their music despite whatever insensitive name they were being called.

***

Phew! A longer essay to start this issue, so I’ll keep it short here. Album of the Week is technically not so new, but I have my reasons why it’s there. Please enjoy the singles but please do enjoy the Oricon revisit, especially if you like Yellow Magic Orchestra. Happy listening!

Album of the Week

Deep Blue by Sora Tob Sakana [NBC Universal]

Recommended track: “Signal” | Listen to it on Spotify

The trajectory of Sora Tob Sakana in the past year has felt a tad uncertain after a member’s graduation reducing the idol group down to a trio, but their music has been more promising than ever. The lack of predictability in their future translated to something more creatively optimistic with last year’s full-length, World Fragment Tour, suggesting that their already-well-defined math-rock sound still had a lot more room to grow. It was a shock, then, to hear the group announce that they will disband this fall after releasing what will be their last full-length album, Deep Blue.

Admittedly, Deep Blue is not entirely new. While it is bookended by two new songs, “Signal” and “Untie,” the rest consists of re-recording of old songs, a good half pulled from their self-titled 2016 album. The new context that surrounds the group, however, transforms the songs from their original state. Familiar lyrics now bear new meanings, and the awe-inspiring music functions with a different purpose. Deep Blue resonates deeper than just a greatest-hits collection, offering a second look at Sora Tob Sakana’s most cherished songs.

The group’s early songs thrived off of innocence and naivete. Part of that came from the idols’ own lack of context with the music they worked with. “In the beginning, we actually sang and performed without understanding that the songs were difficult,” Fuuka Kanzaki said about recording their tracks produced by Yoshimasa Terui, who also leads math-rock-inspired bands such as siraph. Led by their meek voices, Sora Tob Sakana’s self-titled album brought an experience as though you were discovering these new sounds and emotions alongside them. Those sounds unfurl even more vividly thanks to the album’s remastering job, the guitars benefiting the most as the tinny riffs get restored so they can shine as vibrant and dynamic as they should.

Childish innocence fades away from those familiar songs as they return with more experience but also the foresight of their imminent split. The exuberant music once suggested a lush world full of infinite possibilities; now, that same exuberance instead communicates their time rapidly slipping away. “Tick, tock, time still passes by / No one can stop it / Like it will probably go on forever / I’m not a kid anymore.” Such lyrics hits poignant now with their numbered days in mind, and even more when you realize it comes from their first-ever single, “Yozora Wo Zenbu.”

It’s bittersweet to consider that Sora Tob Sakana’s early triumphs have also become their swan song, but Deep Blue ultimately sings a life well lived rather than wallowing in melancholy. The rock music, a mix of wide-eyed electronica and zipping math-rock, still explodes with inimitable energy, and the added polish to the production pumps even more soul for the group’s last hurrah. The idols’ voices, too, have grown sharper, showing off more control of their complex surroundings. Not only do they sound wiser when it comes to articulating their emotions, the three seem unfazed whenever they sing lyrics about the overwhelming speed of life. Sora Tob Sakana accept their time has come to an end, and their embrace of finality inspires a whole new perspective of their music.

Singles Club

“Cream” by macominaming [Oiran Music]

Macominaming’s latest track lulls in and out of a comforting slumber as the glowing synths hum a sleepy tune. The indie-pop duo, too, seems deep in a their dreams as the two softly whisper a verse about how they can’t tell up from down. Their stroll through the subconscious sounds like a delight especially as they get to the hook, stretching out the long syllable of the titular word like sweet taffy.

Listen to the single on Bandcamp.

See also: “Settee” by Newly ft. Kojikoji; “After Five” by O’chawanz

“Yes and No” by Dreams Come True [Universal Sigma]

I started watching the medical TV drama Unsung Cinderella: Midori, The Hospital Pharmacist about a few weeks ago. The episodes remain pretty earnest without too many pockets of comedy, and so I expected a theme song from Dreams Come True that’s just as sincere and sentimental—a mood that the duo have historically nailed with their collection of drama-theme-turned-hits. But as the episode entered its final sappy moments, I noticed, hey, do I hear a break beat? Considering the duo’s jolly asadora entry from last year, a sly inclusion of drum breaks was a big curve ball that I had to investigate a bit further.

“Yes and No” really is one of the edgiest singles to come from the J-pop veterans. R&B has been their foundation since the ‘90s, but the fancy electronic production here is something else. The retro new wave could be easily re-fitted into a synthwave track; if you enjoyed the icy Vangelis synths of The Weeknd’s After Hours, the sleek, cinematic flair of this single should also excite. Miwa Yoshida and her soulful vocals gel well with the lush music, adding a golden feel as though “Yes and No” is a lost pop hit from the opulent ‘80s.

Listen to the single on Spotify.

See also: “Utopia” by AAAMYYY; “Night D” by Eill

“Snooze” by Zombie-Chang [Roman Label / Bayon Production]

Meirin Yung has been playing with electro this year, releasing the resulting one-offs on her YouTube page, and the synth-twiddling experiments come to full fruition in her new Zombie-Chang album, Take Me Away from Tokyo. The spastic electronics such as the one firing off in “Snooze” initially made for more extroverted music relative to her previous output, which seemed conflicting at first with what I enjoy about Yung’s songs. My favorite singles of hers try and fail at fighting against inertia, never quite reaching full catharsis.

The more I immerse myself into the wonky sounds, however, the song becomes as hypnotic as her previous releases with the crowding of noise inviting sensory paralysis. The overwhelm is fitting for such a song with Yung wandering in a half-asleep state while a buzzing alarm echoes in the distance—”gotta shut it off,” she repeats in her signature dead-pan cadence as the iPhone ringer incessantly beeps.

Take Me Away from Tokyo is out now. Listen to it on Spotify.

See also: “Murmur” by Pasocom Music Club; “Turbulence” by Wata Igarashi

This Week in 1981…

“High School Lullaby” by Imo-Kin Trio [For Life, 1981]

No. 1 during the weeks of Aug. 24 - Oct. 5, 1981 | Listen to it on YouTube

The Oricon charts truly feel like the Wild West sometimes with it allowing space for an act like Imo-Kin Trio to climb up to number one. None of the three in the group are musicians but instead talents in entertainment, who starred as regulars in the variety TV program Kindon! Yoiko Waruiko Futsunoko. While TV spawned hits either through a drama series or audition programs, Imo-Kin Trio was one of the first where a variety show assembled their talents to debut a pop group.

The resulting debut single “High School Lullaby” provides a neat look at what was trendy in Japanese pop at the time in 1981. Imo-Kin Trio’s name is a portmanteau of YMO, or Yellow Magic Orchestra, and Johnny’s idol group Tanokin Trio, and the group’s initial make-up essentially resembles what you’d imagine as the other end of that bizarre boy-band formula. The former’s Haruomi Hosono produced the music; the technopop new wave is definitely the work of the master, down to the drum-machine count-in that echoes “Rydeen.” The three sing about their one-sided crush over the skipping electronic beat, the chorus featuring one saccharine hook: “baby, I love you / so suki suki baby,” they call out in unison.

The origin story sets a precedent for a lot of the future TV-born novelty hits in the Oricon. The trio loosely stands as a reference for something like the music career of comedy duo Tunnels, whose star status retroactively feeds into the appeal of the music that they put out on the side during the ‘80s and early ‘90s. The launch of Imo-Kin definitely cast a shadow over the novelty records that came straight from the segments of the Heisei variety program Tunnels No Minasan No Okagedeshita: the debut of Yaen in 1998 from the show essentially updates the YMO rip of “High School Lullaby” into a Kinki Kids parody.

The difference with Imo-Kin is that the members had just got into television with Kindon! and so “High School Lullaby” is propelled more by the trendiness of YMO than necessarily the star power of the involved talents. Conversely, though, it goes to show how the world of Japanese television can launch just about any music career through sheer synergy even if the talents in question have little ambitions to establish themselves in the music realm. The fact that they succeeded using YMO as their vehicle is a cherry on top to one peculiar pop story.

Next issue is out September 2. You can check out previous issues here. You can also find me on Twitter.