Survival Dance: How TRF Turned Eurobeat into the Pop Sound of Japanese City Nightlife

TRF established Eurodance as not just Japanese club music but the soundtrack to city life

Hi! Welcome to Tetsuya Komuro Week at This Side of Japan, a newsletter about Japanese music, new and old. We are dedicating this week on a series of essays discussing the producer’s essential acts and singles. You can return to the Intro page of the series here. You can check out previous issues of the newsletter here.

The night clubs in Tokyo had already been embracing house music imported from Europe by the time Tetsuya Komuro officially launched the TK Rave Factory from then-new record label Avex Trax. Then better known as a member of synth-pop trio T.M. Network, Komuro had been tapped by Avex a few years prior for a dance remix album of his former band’s hits such as “Get Wild.” He soon capitalized on the club scene to debut the dance-pop unit TRF (shortening the Rave Factory moniker) in 1993, and his new group introduced the club experience to the masses who lived far outside the reaches of the famed clubs in the big city.

Before establishing itself as one of the biggest J-pop record labels, Avex Trax mainly operated in the business of promoting Eurodance records. The label opened up shop in 1990 with the then-latest volume of the long-running Super Eurobeat compilations. And by 1993, it sought to bring the experience happening in a nightclub like Maharaja and Juliana’s Tokyo in a live-show format. The resulting endeavor was Avex Rave ‘93 at Tokyo Dome, which hosted acts who specialized in techno, hi-NRG, Eurobeat and other dance genres regularly pumping out of those clubs.

Among the bill of the concert series was TRF. Debuting from Avex Trax a bit before the first Avex Rave, the group had modeled its sound and structure after the many house acts made popular by the famed clubs in Tokyo. The group’s line-up consisted of lead vocalist Yu-Ki, DJ/emcee DJ Koo and back-up singers and dancers Sam, Etsu and Chiharu— practically the Avex Rave stage in miniature. And for its music, their producer Komuro took cues from the various dance genres such as Eurobeat and hardcore techno that Avex already put in work to promote.

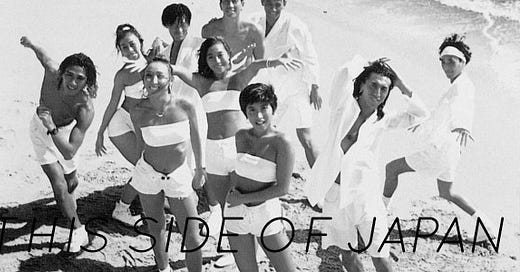

While the first single, “Going 2 Dance,” from the brief Rave Factory days functioned more as a club tool than a pop record. the follow-up, “EZ Do Dance,” saw TRF solidify into a legitimate pop unit. The pumping Eurobeat and Yu-Ki’s diva vocals in “EZ Do Dance” were unmistakably a product of the club, but they adapted their image to fit it in a mold similar to an idol-dance unit when it came to their visual presentation. The single cover art gathers the members not as weekend warriors but dancers at the beach. Watching how the music video focuses on Yu-Ki and her choreography, it’s no surprise the record also brought about exercise tapes.

TRF’s first three albums introduced the mainstream to rave music’s diverse sounds and rhythms, partly with hope from Komuro that the effort would expand Japan’s vocabulary of dance music. His effort to make these sounds commonplace wouldn’t be possible, however, if the producer didn’t make these foreign sounds and rhythms worth engaging with in social contexts other than clubbing. And he stressed accessibility from the start: “Forming TRF, the concept Komuro had was ‘disco plus karaoke, divided by two,’” blogger imdkm wrote in his Real Sound column Thinking in Rhythm with J-pop in 2019. “The ability to sing along to it became as important as the ability to dance along to it.”

The appeal of TRF no longer seemed bound by the ubiquity of club music by the time the group first went platinum with 1994’s “Survival Dance ~No No Cry More~.” The transition into the realms outside of the club, as well as Komuro’s club-and-karaoke concept, began to look apparent in the fifth single, “Samui Yorudakara,” released at the end of 1993. The now-wintertime-classic resides outside of the weekend venues in both sound and content. “I wait for you during these cold nights,” Yu-Ki sings in the titular chorus of a like-ballad dedicated to the forlorn times far after you’ve outgrown the disco.

It’s not to say club music completely fades away recedes in TRF songs. The imported dance sounds still plays a significant part in defining the background context of their narrative-driven songs. In the epochal “Survival Dance ~No No Cry More~,” lyrics about holding on to memories made from a precious night gain resonance laid over a sound attached to the very venues responsible for creating those very memories. “Even if the sun sets, the darkness comes, like an end to a film / it’s never going to end and keep on going, survival dance!,” Yu-Ki grieves. The section hits particularly poignant after discovering how the song played at the last ever set of Juliana’s Tokyo—a destination of legend during the Bubble era before it closed its doors in 1994.

However, TRF had also been putting in work to expand their club-indebted music as the soundtrack to experiences beyond the discotheque and outside the surrounding city. A celebration anthem fitting for an end of an era, the lyrics of “Survival Dance ~No No Cry More~” paint in broad strokes to touch on a general point of making the best of the present. Club music popular in the playlists of the city’s big venues helped establish TRF’s identity. But after TRF, club music had now spilled over as pop music for everyone to enjoy. It’s no longer just imported music but the sound of Japanese night life regardless of location.

Komuro’s work done with TRF adapting club music as a sound of public life continues as he will go on to launch the careers of new pop artists. Through his new acts, he would deepen the narrative and the moods surrounding city life. Meanwhile, the club for TRF becomes more conceptual as a destination to satisfy longing. The group’s “Boy Meets Girl” in 1994 even posits it as a place to graduate from: “those days, I knocked on many doors,” Yu-Ki sings about failed relationships in the past tense before landing on this potentially special one. It also presages the key theme of doomed loneliness prevalent in Komuro’s songs across the decade. At least here, TRF sound optimistic enough to keep on going.

Up next, Part 2: Body Feels Exit: Namie Amuro’s Escape from the City

This Side of Japan has a Ko-Fi as a tip jar if you want to show appreciation. A subscription to This Side of Japan is free, and you don’t have to pay money to access any published content. I appreciate any form of support, but if you want to, you can buy a Coffee to show thanks.

You can return to the Intro page to the series here. You can check out previous issues of the newsletter here.

Need to contact? You can find me on Twitter or reach me at thissideofjapan@gmail.com

Great article! I don’t see a lot of discussion about TRF these days so it’s nice to see some modern appraisal of their work, at least during Komuro’s peak.